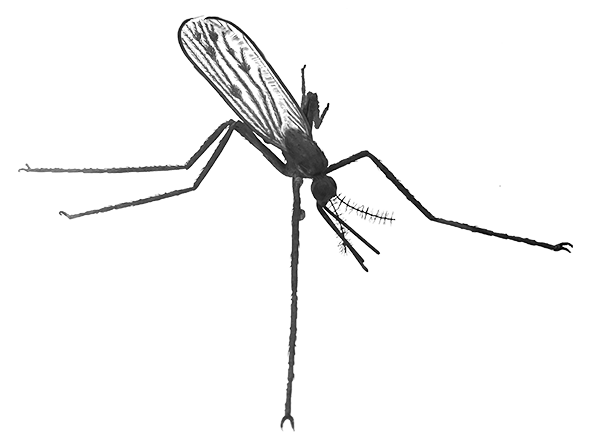

Historian Timothy C. Winegard, in his book Mosquito: A Human History of Our Deadliest Predator, highlights the profound impact of mosquitoes on human history, identifying them as one of the deadliest agents of mortality. Over the course of 200,000 years, approximately 108 billion people have lived on Earth, and nearly 52 billion of them are estimated to have died due to mosquito-borne diseases. This staggering toll reveals the mosquito's unparalleled influence on shaping human civilization, far exceeding the mortality caused by weapons, cancer, or accidents.

Neel Ahuja, environmental humanities scholar examines the deeper socio-political and ecological dimensions of human-animal relations, and comes to a critical perspective on the entangled histories of colonial governance, environmental degradation, and human health. In his essay M is for Mosquito, Ahuja shifts the focus from mortality statistics to the broader ecological disruptions that underpin mosquito-borne diseases. He argues that the mosquito, far from being an isolated agent of disease, is a product of the destabilized ecologies shaped by colonial projects.

“Millions of mosquito bites take place around the world every day. The bug barely catches our attention as we brush it from our faces, arms, or legs. Yet these moments of contact reflect a bigger story about the inherent weakness of a strategy that attempts to manage the colonized environment by viewing nature as an enemy — one that needs to be controlled by science, technology, and bureaucracy. The racist ideas that were used to justify British and U.S. colonization suggested that malaria outbreaks in India, Algeria, Egypt, Panama, and Brazil were the result of underdevelopment and poor hygiene. But the truth is that Euro- American development projects disrupted natural defenses against disease. Colonialism was the source of, rather than the solution to, malaria epidemics. When dams prevent rivers from fertilizing crops, they increase standing pools of water and the need for irrigation and fertilizer. When chemicals are used to control disease, they require dependency on the colonial industries that manufacture and ship chemicals. When doctors advertise that mosquitoes spread malaria, they encourage people to think of humans and nature as divided and at war. Colonialism undermined itself by ravaging the very nature that it sought to appropriate for profit. Mosquito- borne diseases today — from malaria to dengue fever to Zika virus — continue to dominate public health agendas, which suggests that mosquitoes remain effective travelers on the colonial routes of settlement and trade. Settlers were never able to dominate the environments they stole from Indigenous inhabitants. Today, medical researchers and health nonprofits continue to spend large sums of money on drugs, mosquito nets, and chemical repellents to oppose mosquitoes’ evolutionary ability to smell, track, and bite human beings. The lesson, perhaps, is that mosquitoes are not our mortal enemies; they are products of the ecologies we create through forms of development that separate nature from culture, humans from the environment.”

Ahuja, Neel. "M is for Mosquito". Animalia: An Anti-Imperial Bestiary for Our Times, edited by Antoinette Burton and Renisa Mawani, New York, USA: Duke University Press, 2020, pp. 117-124.

Dalmatian Pyrethrum contains natural compounds called pyrethrins, which are highly toxic to insects. When insects come into contact with pyrethrins, these compounds disrupt the nervous system by interfering with the transmission of nerve impulses. Pyrethrins bind to sodium channels in the insect’s nerve cells, preventing them from closing properly after an impulse is transmitted. This causes an uncontrolled influx of sodium ions, leading to overstimulation of the nervous system.

As a result, the insect experiences paralysis. First, it becomes agitated, displaying erratic movements and spasms. Eventually, the paralysis progresses, and the insect is unable to move or breathe properly. This leads to death, typically due to suffocation or a complete breakdown of motor functions. Pyrethrum’s rapid action and neurotoxic effects make it an effective natural insecticide, commonly used in products to control pests like mosquitoes and other insects.

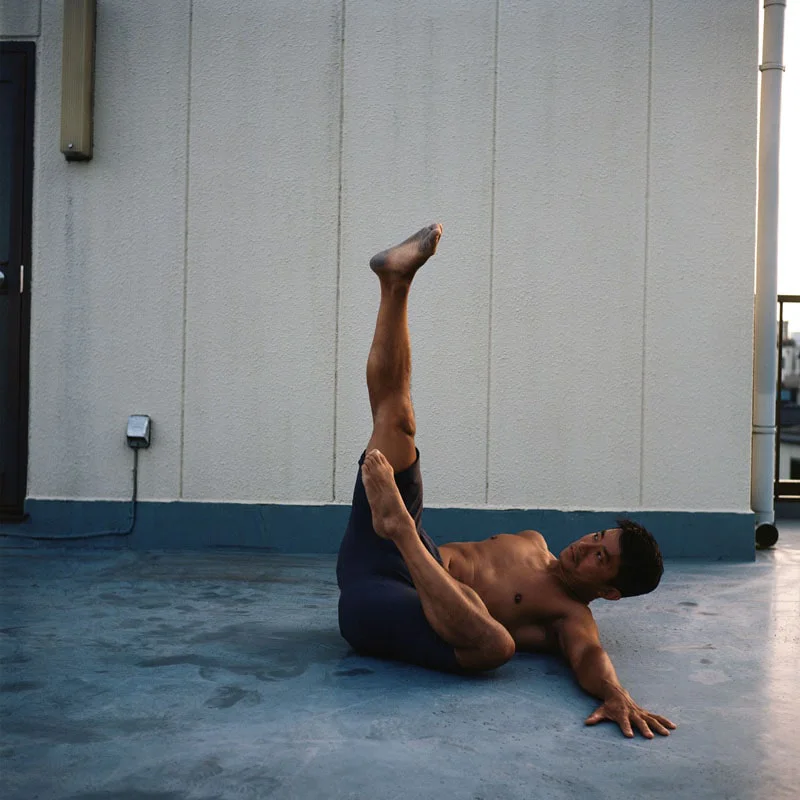

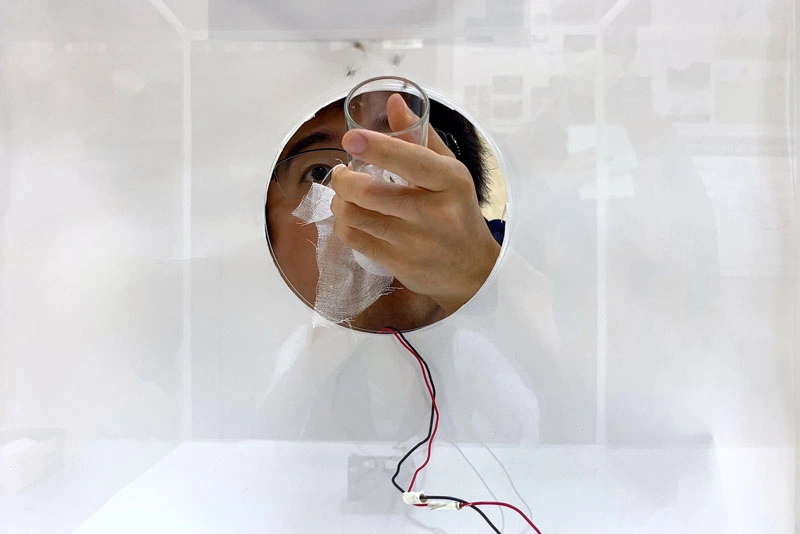

Satoshi Nagae, an exercise physiologist and Tai Chi instructor, demonstrating and speculating about the potential effects of pyrethrins on the human body, using the principles of movement and physiology to explore how these compounds might affect biological systems. Yokohama, 2022